Madison Reid: Seeking Connection

Madison Hope Reid is a multidisciplinary artist and visual designer based in Vancouver, Canada. Her practice explores the intersections of gender, psychology, and power through a feminist lens, often turning the male gaze inward to reveal deeper emotional truths. Since beginning her creative journey at Parsons School of Design in 2008, she has developed a globally informed perspective through residencies in Greece, Mexico, and Germany. Drawing from personal experience, world travel, and a passion for honest dialogue, Reid’s work unearths the complexities of masculinity, femininity, and identity in contemporary culture.

How did your creative journey begin?

I’ve been a creative professional since 2012, working in marketing and design roles. I grew up painting and drawing, but I lost touch with my artistic practices in my 20’s, I think out of frustration or stagnation. Then, in the summer of 2020, I felt compelled to try painting again, so I bought a starter kit of oil paints and had at it. After a year, I started taking weekend workshops and private lessons, and after 2 years, I did my first international residency.

My paintings during the pandemic were mostly landscapes from photos from my travels; I didn’t yet have an artist statement or a defined voice, but the act of making helped me feel tethered to myself again. Over the years, I saved a few screenshots from Tinder and Bumble to my phone—strange, unflattering, confusing images—and kept wondering, what happens if I paint these? What do they reveal when they’re taken seriously as portraits?

So I rendered these funny photos into oil, and what began as just a couple quick portraits gradually evolved into a larger body of work, and eventually an entire thesis dedicated to how men construct and perform their masculinity. WIth time, my own feelings of alienation and disillusionment began to surface in my work. I realized I wasn’t just analyzing masculinity but responding to the experience of feeling invisible, bored, or emotionally underwhelmed in a world that feels engineered to disappoint.

That sense of emotional disconnection, like being a participant in modern intimacy while also observing it from the outside, is what’s pushing my work forward.

Your work interrogates the male gaze from a feminist perspective. How has your own experience of gender shaped the lens through which you create?

I think, like many women, I feel hyper aware of how the world perceives me. And I am also hyper aware of how our culture perceives women through art and media. We exist in the narrow confines of what has been deemed desirable by the heterosexual male gaze. And it’s insidious—in my teens and 20’s, being seen as desirable was the most valuable thing I could be. I internalized it deeply. Now I’m spending the rest of my life working to reject this concept.

So, the question that my practice frequently asks is whether (hetero) men feel equally aware of how they are being perceived? And who are they performing for when they try to be desirable? Is it women, or in fact, other men, that are the dictators of desire?

Cars are a great example of this, and my ‘Autonomous’ series was about men’s relationships with his car. I used the dating apps to match with men who had pictures of their cars in their profiles and ask them questions—if they felt their car was a representation of who they are, and how they wanted to be seen by a prospective girlfriend. One guy candidly said that it actually terrified him to think of how a woman might see him. I don’t think he’d ever thought about it before, which I thought was wild. You’ve really never considered how you might be perceived? Wow, that must be nice.

There are many ways to make feminist art. For me, it’s about turning the gaze back on itself—holding up a mirror and inviting men to look at themselves with discomfort and curiosity. I’m trying to reclaim space for my own voice, my own longing, and my own alienation. I want to speak unapologetically about my experiences without prioritizing the comfort of others.

You mention your paintings have moved from more literal depictions to a “looser accumulation of marks and color and gesture.” What sparked that shift? Was it intuitive or deliberate?

The shift comes from my evolution to becoming more of a conceptual artist. I want the work to pose questions to the viewer, rather than produce something static. It’s less about “finishing” something and more about letting the work unfold in real time.

What does a typical day in the studio look like for you, and how has your art practice grown or changed?

A typical day in the studio might involve painting, or scrolling through my iPad’s camera roll for inspiration, or 30 minutes of sitting on the couch and just staring at the ceiling. Studio time does not need to equal output—I’m realizing the input stage might actually be more important.

In the early years of my practice, I was strictly a painter. Painting gave me structure—a frame to work within, materials I could control, a quiet space to process my emotions through image and form. It also gave me permission to call myself an artist. But over time, I’ve discovered a love of accessible, sometimes guerilla forms of art. Art that the masses can find and engage with on their own terms. So, in my famished, novelty-starved state, I started putting up posters of my face around Vancouver with the headline “Seeking the perfect man”. In true artist form, I stole the idea from another artist (@marcinglod), who’d stolen it from the OG: Dan Perino of New York, who apparently has put up over 20,000 flyers over the last decade (and last I checked, still hasn’t found his perfect woman).

I’m now more interested in the process, the tension, and the blurry space between sincerity and satire. Will the results of my search for the perfect man be a zine, some paintings, or true love and human connection? It doesn’t really matter; I just want to see what happens in the meantime.

Are there particular painters—historical or contemporary—that continue to inform your choices with color, brushwork, or composition?

I have respect and admiration for Jenny Saville, who is reclaiming the female form and does it on such a massive scale. I am a huge fan of Doron Langberg, particularly when it comes to his brushwork and colour choices, but also his queer subjects that depict men in intimate and vulnerable spaces. Other artists that stay front of mind are Andy Dixon, who mixes classical subject matter in a very contemporary palette and style, Willem de Kooning, and Henri Matisse.

How has social media impacted your work?

I’ve received Instagram messages from friends and former classmates I haven’t spoken to in decades saying that they love seeing my process and how my work has changed over time, which helps me realize that what I’m doing is bigger than myself. I need that reminder.

I posted one of my paintings from ‘Autonomous’ for sale on Facebook marketplace last year; it was a painting of Nathaniel and his car Chase from TLC’s My Strange Addiction. The ad ended up going viral and got over 35K clicks, and I got over 50 messages from total strangers that were thanking me, saying it was the best thing they’d ever seen, that I was doing God’s work. The act of selling the painting ended up being its own social experiment, and helped nudge me towards finally starting my Perfect Man project and crowdsource reactions.

As a multidisciplinary artist and designer, how do you decide which medium to use for a particular concept or body of work?

If I need to visually depict something, painting is what comes easiest to me. But the decision process is mostly just me jotting down my thoughts and ideas, and thinking of how I want my questions to be asked.

The first time I showed my paintings, I didn’t feel like they were going to be absurd enough on their own. To really sell the feeling of disillusionment, I created fake dating profiles that accompanied each piece that viewers could open by scanning a QR code. Even though each painting had a respective QR code, the profiles had nothing to do with what was depicted in the piece, kind of capturing that feeling of disconnect and confusion when using the dating apps.

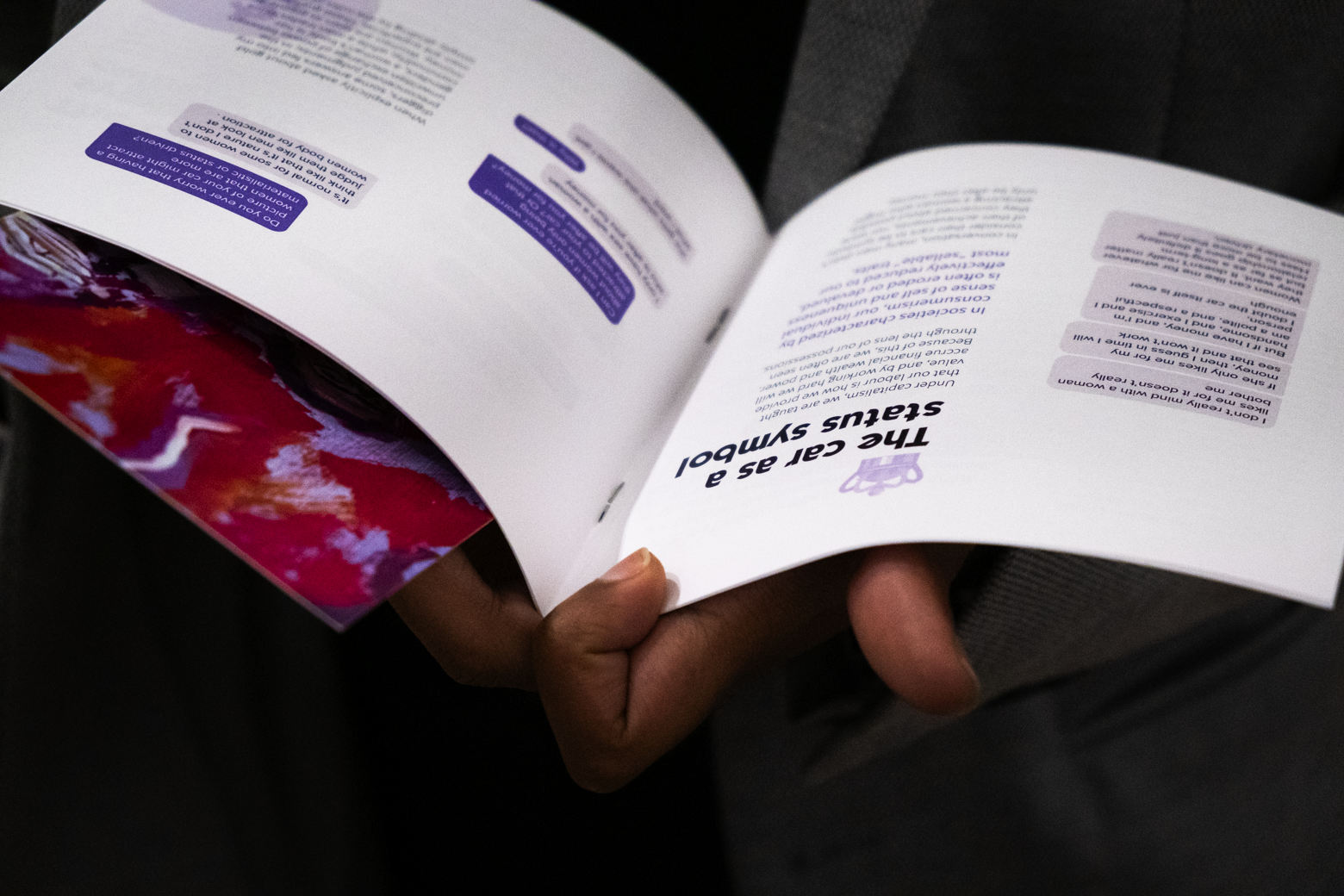

For my ‘Autonomous’ show, in addition to showing some paintings, I designed some zines that included my “research” (the conversations with men from Tinder) because that component was the meat of the project. If and when I do a show on my search for the Perfect Man, I’d like to use generative AI to share some of the voice mails I’ve received. I want to take advantage of generative AI while it’s still clunky and kind of shitty because real life also feels like an uncanny valley.

What kind of conversations do you hope your work initiates—especially around gender, identity, or intimacy?

The most frequent reaction viewers have to my (Tinder portrait) paintings is “why would someone think that’s attractive?” I tell them that I’ve built a whole practice around trying to answer that question.

As I shift away from the subject of dating apps and more toward the broader search for connection and intimacy, I want my work to initiate conversations about how we (as humans) perform ourselves when we want to be seen, what we’ve internalized from media and algorithms, and why vulnerability feels so high-stakes and risky. But if all I’m making others do is cringe and laugh, that’s fine too. Sometimes the most honest entry point into a deeper conversation is through a bit of secondhand embarrassment.